Karbala:

The Tragedy & Triumph of

Husayn Ibn Ali (P)

WHAT IS KARBALA?

The tombs at Karbala stand magnificently unperturbed with their resplendent gold cupolas, ornate silver mausoleum cages, gold-plated and enameled cedar doors, marble floors, Persian carpets, velvet curtains, crystal chandeliers, mirrored walls, and air filled with the fragrance of incense and attar. Yet, almost 1500 years later, the gaze of the pilgrim pierces through all this grandeur and sees, instead, the broken bones of Husayn’s trampled body, the severed heads, the mutilated, dismembered, and bloodied bodies, the wailing thirsty children, the burning tents, terrorized women running out of the fiery blaze, vile soldiers slapping the cheeks of panicked children, the welts and bruises on the bodies of prisoners, the unfurled whips, the clanging chains . . .

And more than anything, the pilgrim hears loud and clear Husayn’s call hal min naaserin yansurna (“is there anyone to help me?”) and so the pilgrim cries out Labbaik Yaa Husayn, Labbaik Yaa Husayn (“I am here O Husayn, I am here”) . . .

Karbala is a city in central Iraq approximately 55 miles (88 km) southwest of Baghdad. With a barren terrain common to the region, a population of less than one million, extremely hot climate, and no natural resources or landmarks to boast, this city should have been unremarkable. But it is not.

It is not because a battle took place on this land in 680 ce, which put Karbala prominently on the world map for eternity.

The battle of Karbala was fought on October 10, 680 ce. In this battle, Husayn ibn Ali (p), the grandson of the Holy Prophet Muhammed (p), and his small party of 72 men were massacred by a massive force sent by the Umayyad king Yazid I (also known as Yazid the Tyrant) who ruled from his throne in Damascus, Syria.

Having ascended the Damascus throne on April 21, 680 ce (following the death of his father Mu’awyia), Yazid recognized that in order to legitimize his rule as a caliph of all Muslims, he needed a pledge of allegiance from the only surviving grandson of the Holy Prophet (p). He instructed Walid ibn Utba, the Ummayad governor of the city of Medina (Husayn’s birthplace and hometown) to demand that Husayn pledge allegiance to Yazid, using force if necessary. Husayn was summoned in the late hours of the night to the palace of Walid and a demand for allegiance was made. Referring to the corrupt, vulgar, and decadent rule of the Ummayads, Husayn declined stating that “a person like me can never pledge allegiance to a person like Yazid.”

Facing increasing pressure in Medina, Husayn left his home town and arrived in the city of Mecca in early May 680 ce. Although he had planned on staying in Mecca for the upcoming Hajj pilgrimage, he left Mecca on September 9, 680 ce, a day before start of the Hajj. Yazid had sent assassins in the guise of pilgrims and Husayn abhorred the thought of bloodshed in the confines of Mecca.

With a small caravan that included women and children, he headed toward the city of Kufa, Iraq. En route to Kufa, he was intercepted by Yazid’s army and forced to change his direction toward Karbala. He arrived in Karbala on October 3, 680 ce and set up his tents on the banks of the Euphrates. Under the leadership of Umar ibn Sa'd, Yazid’s army demanded that Husayn move his tents far from the river banks. As part of an effort to force Husayn to pledge allegiance to Yazid, Husayn and his followers were denied access to the river. By October 7th, whatever water Husayn’s camp had in storage had depleted. The sounds of children crying out for water could be heard in the camps of Yazid’s army.

Battalions of soldiers began arriving to join Yazid’s army including 30,000 horsemen led by the governor of Kufa, Ubaydallah ibn Ziyad. In the early morning hours on October 10th Yazid’s army began shooting arrows at Husayn’s camp signaling the start of war. Several companions of Husayn were killed by these arrows while in prayer. Following completion of morning prayers, Husayn’s brother, his son, his nephews and his friends, all of whom had had no water for three days, took turns fighting Yazid’s army and were killed. Husayn then took his six month old son into the battlefield and asked that the baby’s thirst be quenched. Under orders from Umar ibn Sa'd, Hurmula ibn Kahin shot a three-pronged arrow at the baby’s neck. Husayn buried the baby in the desert sands and returned to the battlefield. By now it was close to sundown. He called out hal min naaserin yansurna (“Is there anyone to help me?”) which call was greeted with jeers from Yazid’s army.

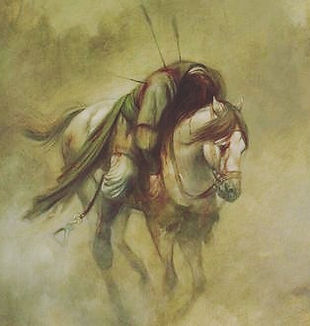

Husayn faced the massive army alone. He had been without water for days and had witnessed the violent deaths of his sons, brother, nephews, and friends. Yet, historians note that he fought valiantly and when he fell from his horse, so many arrows had pierced his body that he looked like a porcupine. Surrounded by violent, blood-thirsty men including Shimr ibn Zil Jawshan and Umar ibn Saad, Husayn was beheaded on the desert floor.

_jfif.jpg)

LEARN MORE:

Husayn’s armor was plundered, his body was trampled by horses, his tents were ransacked and torched, the chaddors (hijabs/coverings) of his women were looted, and his remaining family members, the majority of whom were women and children, were bound in ropes and chains. The buried body of the six month old baby was dug up and beheaded. The severed heads of Husayn, his sons, brother, nephews, and friends were placed on spears and, along with his imprisoned family, were paraded through the streets and bazaars of Kufa and Damascus. Following a presentation before Yazid at his opulent court in Damascus, Husayn’s family was imprisoned in the dungeons of Yazid’s prison. Husayn’s four year old daughter Sukayna (p) died and was buried in the prison.

Although Yazid succeeded in killing Husayn violently and in unleashing untold ferocity upon him and his family, Yazid never did get from Husayn what he had so brutally and desperately sought – the elusive pledge of allegiance. Thus, while remaining an unforgettable reminder of the tragic massacre of Husayn, Karbala is also a resounding proclamation of Husayn’s triumph.

VIEWS ON KARBALA

“The tragedy of Karbala decided not only the fate of the caliphate, but of the Mohammedan kingdoms long after the Caliphate had waned and disappeared.” Sir William Muir (1819-1905), the Scottish scholar and statesman, Annals of the Early Caliphate, London, 1883, pp. 441-2.

“… a reminder of the blood-stained field of Kerbela, where the grandson of the Apostle of God fell at length, tortured by thirst and surrounded by the bodies of his murdered kinsmen, has been at anytime since then sufficient to evoke, even in the most lukewarm and heedless, the deepest emotions, the most frantic grief, and an exaltation of spirit before which pain, danger and death shrink to unconsidered trifles.” Edward G. Brown, professor of Arabic and oriental studies at the University of Cambridge, A Literary History of Persia, London, 1919, p. 227.

“Then Husain mounted his horse, and took the Koran and laid it before him, and, coming up to the people, invited them to the performances of their duty: adding, ‘O God, thou art my confidence in every trouble, and my hope in all adversity!’… He next reminded them of his excellencies, the nobility of his birth, the greatness of his power, and his high descent, and said, ‘Consider with yourselves whether or not such a man as I am is not better than you; I who am the son of your prophet’s daughter, besides whom there is no other upon the face of the earth. Ali was my father; Jaafar and Hamza, the chief of the martyrs, were both my uncles; and the apostle of God, upon whom be peace, said both of me and my brother, that we were the chief of the youth of paradise. If you will believe me, what I say is true, for by God, I never told a lie in earnest since I had my understanding; for God hates a lie. If you do not believe me, ask the companions of the apostle of God [here he named them], and they will tell you the same. Let me go back to what I have.’ They asked, ‘What hindered him from being ruled by the rest of his relations.’ He answered, ‘God forbid that I should set my hand to the resignation of my right after a slavish manner. I have recourse to God from every tyrant that doth not believe in the day of account.'” Simon Ockley (1678-1720), professor of Arabic at the University of Cambridge, The History of the Saracens, London, 1894, pp. 404-5.

“Ever since the black day of Karbala, the history of this family … has been a continuous series of sufferings and persecutions. These are narrated in poetry and prose, in a richly cultivated literature of martyrologies – a Shi’i specialty – and form the theme of Shi’i gatherings in the first third of the month of Muharram, whose tenth day (‘ashura) is kept as the anniversary of the tragedy at Karbala. Scenes of that tragedy are also presented on this day of commemoration in dramatic form (ta’ziya). ‘Our feast days are our assemblies of mourning.’ So concludes a poem by a prince of Shi’i disposition recalling the many mihan of the Prophet’s family. Weeping and lamentation over the evils and persecutions suffered by the ‘Alid family, and mourning for its martyrs: these are things from which loyal supporters of the cause cannot cease. ‘More touching than the tears of the Shi’is’ has even become an Arabic proverb.” Ignaz Goldziher (1850-1921), Hungarian orientalist scholar, Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law, Princeton, 1981, p. 179.

“In a distant age and climate the tragic scene of the death of Husain will awaken the sympathy of the coldest reader.” Edward Gibbon (1737-1794), considered the greatest British historian of his time, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, London, 1911, volume 5, pp. 391-2.

“Hussein accepted and set out from Mecca with his family and an entourage of about seventy followers. But on the plain of Kerbela they were caught in an ambush set by the … caliph, Yazid. Though defeat was certain, Hussein refused to pay homage to him. Surrounded by a great enemy force, Hussein and his company existed without water for ten days in the burning desert of Kerbela. Finally Hussein, the adults and some male children of his family and his companions were cut to bits by the arrows and swords of Yazid’s army; his women and remaining children were taken as captives to Yazid in Damascus. The renowned historian Abu Reyhan al-Biruni states; “… then fire was set to their camp and the bodies were trampled by the hoofs of the horses; nobody in the history of the human kind has seen such atrocities.” Peter J. Chelkowski, professor of Middle Eastern Studies, New York University, Ta’ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran, New York, 1979, p. 2.

“Husayn fell, pierced by an arrow, and his brave followers were cut down beside him to the last man. Muhammadan tradition, which with rare exceptions is uniformly hostile to the Umayyad dynasty, regards Husayn as a martyr and Yazid as his murderer.” Reynold Alleyne Nicholson (1868-1945), A Literary History of the Arabs, Cambridge, 1930, p. 197.

“Hosain had a child named Abdallah, only a year old. He had accompanied his father in this terrible march. Touched by its cries, he took the infant in his arms and wept. At that instant, a shaft from the hostile ranks pierced the child’s ear, and it expired in his father’s arms. Hosain placed the little corpse upon the ground. ‘We come from God, and we return to Him!’ he cried; ‘O Lord, give me strength to bear these misfortunes!’ … Faint with thirst, and exhausted with wounds, he fought with desperate courage, slaying several of his antagonists. At last he was cut down from behind; at the same instance a lance was thrust through his back and bore him to the ground; as the dealer of this last blow withdrew his weapon, the ill-fated son of Ali rolled over a corpse. The head was severed from the trunk; the trunk was trampled under the hoofs of the victors’ horses; and the next morning the women and a surviving infant son were carried away to Koufa. The bodies of Hosain and his followers were left unburied on the spot where they fell. For three days they remained exposed to the sun and the night dews, the vultures and the prowling animals of the waste; but then the inhabitants of a neighboring village, struck with horror that the body of a grandson of the Prophet should be thus shamefully abandoned to the unclean beasts of the field, dared the anger of Obaidallah, and interred the body of the martyr and those of his heroic friends.” Robert Durey Osborn (1835-1889), the Major of the Bengal Staff Corps, Islam Under the Arabs, Delaware, 1976, pp. 126-7.